KisS: A programme to prevent sexual aggression in young adults

- Article

- Bibliography information

- Authors

- Complete issue

Theoretical basis of the KisS intervention programme

Numerous studies have shown that both the experience and perpetration of sexual aggression, defined as sexual acts without consent, are widespread among young adults (Krahé & Berger, 2013; Krahé et al., 2021). Research has also shown that sexual victimisation has various negative consequences for the mental and physical health of those affected (Krahé & Berger, 2017).

Therefore, there is a clear need to develop and systematically evaluate prevention programmes that are evidence-based and backed up by solid theory. This means that interventions should focus on those variables identified as risk factors of perpetration and vulnerability factors of sexual victimisation – and changeable through targeted measures. The “Kompetenz in sexuellen Situationen” (KisS; Competence in Sexual Situations) programme we developed is based on such an approach.

Our research indicates that a key to understanding sexual aggression lies in the behavioural “scripts” for consensual sexual interactions. Sexual scripts contain mental representations of the typical and desired characteristics of sexual interactions that guide sexual behaviour. Regarding sexual aggression and victimisation, sexual scripts can be classified as “risky” if they contain established risk factors for sexual aggression and vulnerability factors for victimisation. These include (a) engaging in sexual contacts with people one knows hardly or not at all, (b) consuming alcohol during sexual interactions and (c) the ambiguous communication of sexual intentions, e.g., saying “no” even though sexual contact is desired.

The more firmly these characteristics are represented in the scripts for consensual sexual interactions, the more likely they will be realised in sexual behaviour, which in turn increases the likelihood of engaging in and experiencing sexual aggression. We demonstrated these pathways in longitudinal studies with young adults in several countries (D’Abreu & Krahé, 2014; Krahé & Berger, 2021; Schuster & Krahé, 2019a,b; Tomaszewska & Krahé, 2018).

Other predictors of sexual aggression and victimisation include low sexual self-esteem and low sexual assertiveness, defined as the ability to reject unwanted sexual advances (rejection assertiveness) and to initiate consensual sexual contact (initiation assertiveness; Morokoff et al., 1997). In addition, the extent to which the use of coercion to achieve sexual goals is considered acceptable was shown to be a predictor of sexual aggression. Finally, previous research also indicates that the perception of pornographic depictions as realistic – weighted by the frequency of consumption – is associated with an increased likelihood of sexual aggression and victimisation (Krahé et al., 2022). These risk and vulnerability factors formed the basis for the development of our intervention programme KisS, which was specifically geared towards the following objectives:

(1) Modifying risky sexual scripts for consensual contact: After the intervention, participants should be less convinced that sexual contact with people they hardly know or do not know at all, the consumption of alcohol in sexual interactions and the ambiguous communication of sexual intentions are typical and desirable characteristics of consensual sexual encounters.

(2) Reducing sexual risk behaviour: Participants should consume alcohol less often in subsequent sexual interactions, communicate their sexual intentions more clearly and have sex less often with partners they hardly know or do not know at all.

(3) Promoting sexual self-esteem in the sense of a positive image of one’s own sexuality as well as assertiveness in rejecting unwanted and initiating desired sexual contact.

(4) Reducing the acceptance of coercion in sexual interactions.

(5) Reducing the perception of pornographic images as realistic.

(6) Reducing the probability of perpetrating and experiencing sexual aggression over a longer follow-up period by changing the constructs mentioned under 1 to 5.

Design, content and implementation of the KisS programme

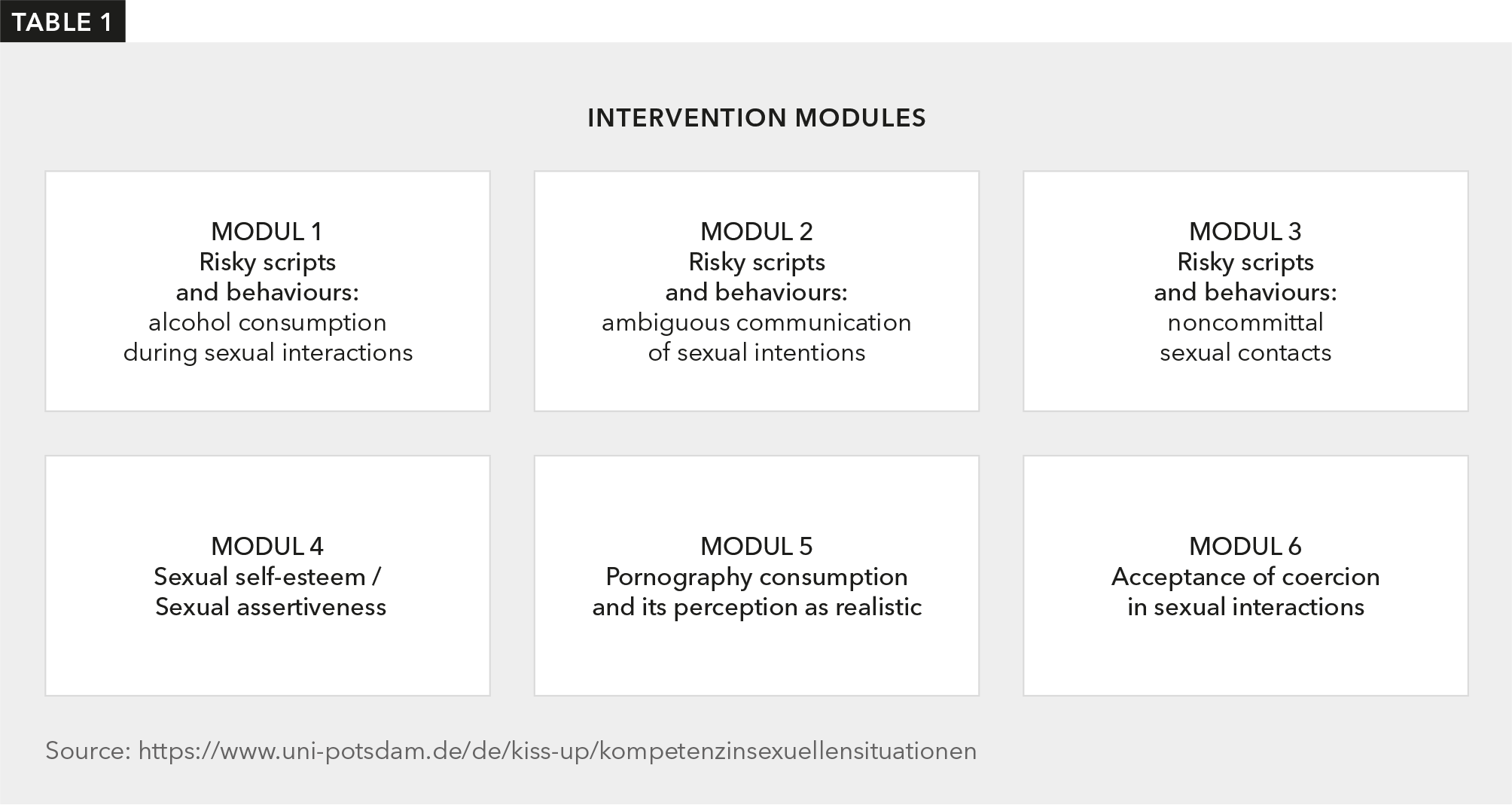

The programme was designed as an online intervention to promote sexual competence, as it was intended not only to focus on the prevention of sexual aggression but also to promote various important aspects of competence regarding the positive shaping of consensual sexual relationships. Table 1 lists a total of six thematic modules.

Didactically, the modules are based on a psycho-educational approach It consists of a combination of scenarios of sexual interactions in which participants are encouraged to put themselves, the provision of information, e.g., on the effect of alcohol on information processing, and self-reflection exercises as well as other tasks to be completed between the modules, e.g., discussions with friends on topics such as the reality content of pornographic depictions of sexuality. The suitability of the materials for changing the target constructs was tested in a pilot study. We assigned different versions of the modules to the participants depending on their gender and previous sexual experiences. For example, women who reported only heterosexual contacts were given scenarios with heterosexual interactions from a female perspective.

A total of 1,181 students (762 women, 419 men) from universities in Berlin and Brandenburg took part in the study to evaluate the KisS programme. The average age at the first data wave (T1) was 22.6 years. Participants were randomly allocated to the intervention and control conditions. We measured the risk and vulnerability factors using established instruments based on self-report and self-assessment, as described in Schuster et al. (2022). We assessed sexual aggression using the Sexual Aggression and Victimization Scales (SAV-S; Krahé & Berger, 2014). This instrument records sexual aggression perpetration and victimisation with 36 parallel items, respectively, which differentiate between three coercive strategies (verbal pressure, exploiting the inability to resist, and threat or use of physical violence), three relationship constellations (current or former partner, friend or acquaintance, stranger) and four sexual acts (sexual touching, attempted and completed penetration of the body, other sexual acts).

Both the intervention group and the control group completed the measures of risk factors and sexual aggression and victimisation at T1. The intervention group received the first module of the intervention programme immediately afterwards, the other five modules followed in weekly intervals. One week after completion of the last module (T2), all participants completed the cognitive measures again (sexual scripts, sexual self-esteem and acceptance of pressure). Nine months later (T3), they completed these measures once again, together with risky sexual behaviour, pornography consumption and the perception of pornography as realistic as well as sexual perpetration and victimisation. 12 months later (T4), we again collected these measures from all participants. The study thus covered a total period of 23 months. At T4, 81 % of the initial sample still participated in the survey, a very high retention rate. Participation in the study was credited with Amazon vouchers.

Results

First of all, this study joined earlier research in identifying high prevalence rates of sexual victimisation: 62.1 % of the women and 37.5 % of the men reported at T1 that they had experienced at least one sexual experience against their will across various forms of coercion since the age of 14. A total of 17.7 % of men and 9.4 % of women stated that they had made another person engage in sexual acts against their will at least once.

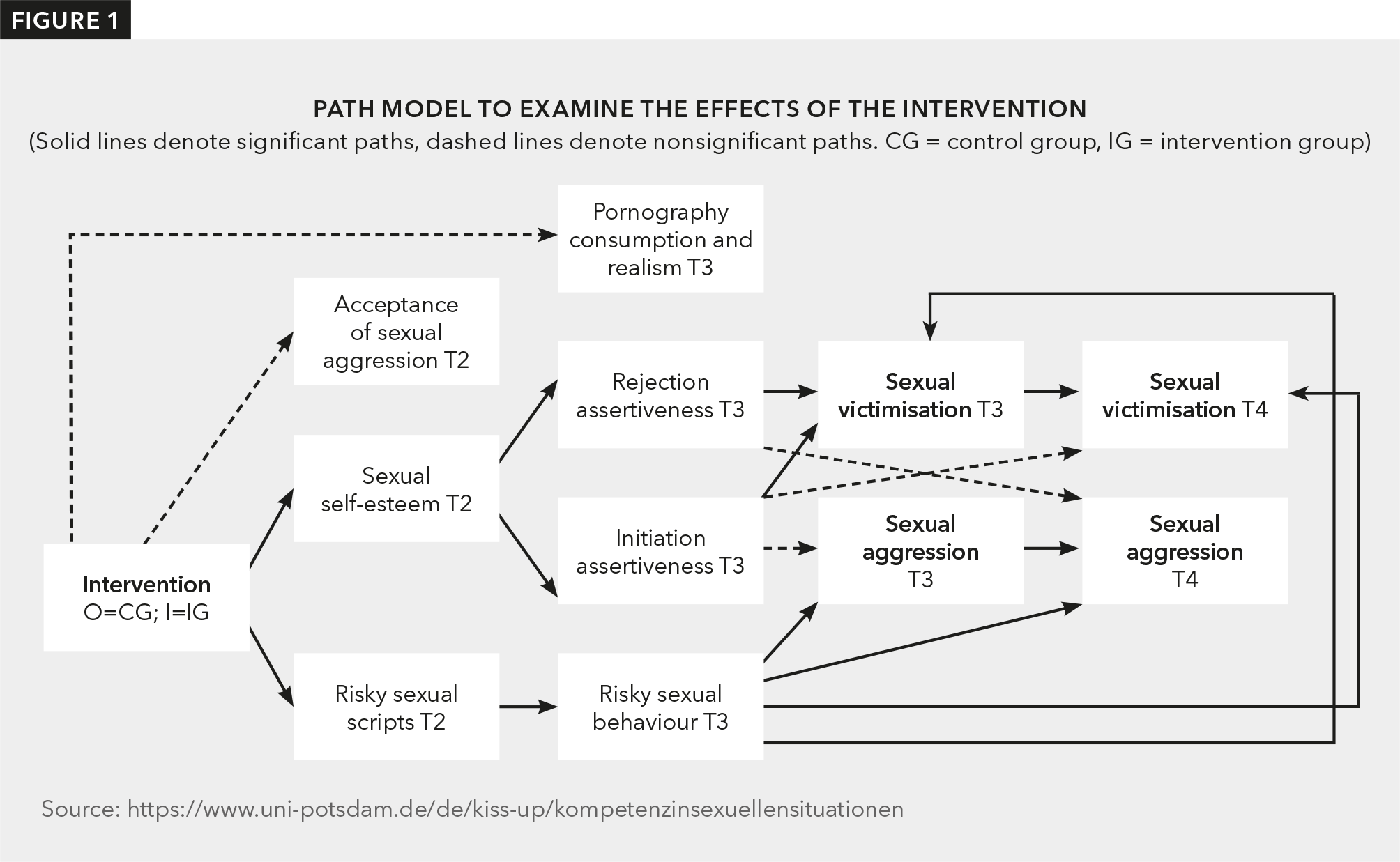

The rates of perpetrating and experiencing sexual aggression did not differ significantly between the intervention and control groups at the two follow-up time points T3 and T4. However, we had not predicted direct effects of the intervention but rather hypothesized an indirect effect via the identified risk and vulnerability factors. Accordingly, we tested the effectiveness of the intervention in three steps.

In the first step, we investigated whether the cognitive risk factors recorded at T2 (sexual scripts, sexual self-esteem, acceptance of coercion in sexual interactions) were less pronounced in the intervention group – taking into account the respective baseline values before the intervention – and whether these reduced levels were still detectable at T3 and T4. This analysis revealed that the participants in the intervention group had significantly less risky sexual scripts and significantly higher sexual self-esteem at all three time points after the intervention than the participants in the control group. It also became clear that the effect of the intervention on risky sexual scripts was particularly pronounced in those participants who already had medium and high levels of risky scripts before the intervention. There was no significant difference between the intervention and control groups regarding acceptance of coercion in sexual interactions.

In the second step, we tested the predicted indirect effect of the intervention on sexual risk behaviour, sexual assertiveness and the perception of pornography as realistic, mediated by the sexuality-related constructs of sexual scripts and sexual self-esteem considered in the first step. Here, too, the findings were predominantly consistent with our predictions. Nine months (T3) and 21 months (T4) after the intervention, participants with less risky sexual scripts at T2 showed less sexual risk behaviour. Higher sexual self-esteem at T2 predicted higher assertiveness in initiating and rejecting sexual contact at T3 and T4. We found no effects regarding the evaluation of pornographic depictions as realistic.

Finally, in the third step, we investigated the indirect effects of the intervention on the probability of perpetrating and experiencing sexual aggression, mediated by the cognitive (sexual scripts and sexual self-esteem) and behavioural (sexual risk behaviour and sexual assertiveness) factors influenced by the intervention. The impact of the intervention on sexual scripts proved to be particularly relevant. Mediated by less risky behaviour at T3, less risky sexual scripts like those found in the intervention group at T2 predicted a significantly lower probability of engaging in, and experiencing, sexual aggression at T3 and T4. The effect of the intervention on sexual self-esteem only led to a lower probability of sexual victimisation at T3 via increased assertiveness in initiating sexual contact. There were no significant gender differences. Further, there were no effects on sexual victimisation via increased rejection assertiveness, nor were there any effects via this path on the probability of sexual aggression. Figure 1 summarises the results.

Discussion and outlook

The results largely confirm the expected impact of the intervention. Reducing risky sexual scripts lowered the probability of sexual aggression and sexual victimisation significantly by reducing risky sexual behaviour. In addition, by promoting sexual self-esteem, assertiveness for rejecting unwanted and initiating desired sexual contact was increased. Finally, there was also an indirect effect of higher sexual self-esteem on reducing the likelihood of sexual victimisation, mediated by higher initiation assertiveness. However, we were unable to achieve any intervention effects regarding the change in the acceptance of coercion in sexual interactions and the evaluation of pornography as realistic. Nevertheless, we consider the programme to be successful overall, especially since the sustainable effects on sexual scripts, sexual risk behaviour, sexual self-esteem and sexual assertiveness over the entire duration of the programme reflect an increase in competence and satisfaction in sexual relationships beyond the problem of sexual aggression. In addition, large parts of the second follow-up period occurred during the time of Covid-related contact restrictions, which reduced the overall opportunities for sexual contact and thus also the likelihood of sexual aggression perpetration and victimisation.

The next step would be to revise modules 5 (consumption and perception of pornography as realistic) and 6 (acceptance of coercion in sexual interactions) and to identify reasons for the lack of effectiveness. Because the intervention and the instruments for measuring effectiveness can be presented entirely online, the KisS programme is also suitable for efficient use in a decentralised manner and with larger groups.

Citation

Krahé, B., Tomaszewska, P., & Schuster, I. (2023). KisS: A programme to prevent sexual aggression in young adults, FORUM sexuality education and family planning: information service of the Federal Centre for Health Education (BZgA), 1, 45–50.

Publication date

Prof. Barbara Krahé is Professor Emerita of Social Psychology at the University of Potsdam. Her research focusses on the topics of sexual aggression and the effects of media violence.

Contact: krahe(at)uni-potsdam.de

Dr Paulina Tomaszewska was a Researcher at the Chair of Social Psychology at the University of Potsdam until 2022. She is now a psychotherapist specialising in behavioural therapy.

Dr Isabell Schuster is a Lecturer in the Department of Emotional and Social Development at the Free University of Berlin. One focus of her work is the prevention of sexual aggression in adolescence and adulthood.

All links and author details refer to the publication date of the respective print edition and are not updated.

Issuing institution

In issue

- Gender roles, housework, couple conflicts. A first look at FReDA – The German Family Demography Panel Study

- Parents' views on their children's sexuality education. Results of the BZgA study on Youth Sexuality

- Unwanted pregnancies over the life course – Results of the “women´s lives 3” study

- A comparison of reproduction policy across countries: A new international database

- Pioneering change: ANSER's impact linking research and policy on sexual and reproductive health

- Online pregnancy termination videos: Providers, messages and audience reactions

- KisS: A programme to prevent sexual aggression in young adults

- Sexualised violence in adolescence – A comparison of three representative studies

- “How are you doing?” The psychosocial health and well-being of LGBTIQ* people

- Experiences with §219 pregnancy advice by phone or video. Client perspectives

- The relevance of sexual rights in family and schoolbased sexuality education in Switzerland

- School sexuality education from the perspective of the target group

- Impediments to accessing contraception in asylum centres: The perspectives of refugee women in Switzerland

- The EMSA study: Sexual debut, menstruation and pregnancy termination on social media

- Sexuality education in primary school: A survey of teachers using a mixed-methods design

- The EU project PERCH: A united fight against HPV-related cancer

- The Erasmus+ project: Sexuality education for adolescents and young adults with a refugee background

- Safe Clubs: A transfer project for the prevention of sexualised violence in sport

- Incurably queer? An approach to research on conversion therapies in Germany

- The LeSuBiA study: Life situation, safety and stress in everyday life